"I'm going to post Montana next, for my own reasons. Then, perhaps, the rest of the driving trip.

And then, perhaps, I think I'll rest a little.

By making my brother write for me.

"

Saturday, November 25, 2006

(By Way of Explanation)

Thursday, November 16, 2006

The Back Catalog

I can't believe it's been a month since I posted here...it's shocking, really.

In any case, I placed a review in the Chronicle way back in October that I thought I'd link to:

Detective from central casting investigates a suspect from same place

I just saw this, honestly, and I've only skimmed it, but I can say that it was definitely edited...I don't mind that, but it's good to note.

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Thursday, October 19, 2006

Friday, October 13, 2006

Another Day, another article

I have another book review up at sfstation now, of Chris Adrian's The Children's Hospital. You can read it here.

Sunday, October 01, 2006

Montana, Day One

Zander, who is driving to the airport, is 5 minutes early, and it's 4:40 in the morning. I've been up since 4:15, and Dad's been up since even earlier, but neither of us is what you would call cheery.

Cheery, however, is exactly how you would describe Zander. He's a contractor and a mountain climber, and his joie de vivre—when he's excited and things are going well—is often infectious.

But infectiously cheery is not necessarily what I want at any time before 5 am. Or 6 am. Or 8 am, really. Nonetheless I bite my tongue, stuff the last of my clothes into a duffel bag, and Dad and I climb into the back seat of Zander's pickup, with Wendy, Zander's wife, in front.

We pick up Bob and Dawn a few minutes later, maybe a mile east. I've never met them before, and now we are all crammed together in Zander's truck, speeding down the mostly empty freeway to SFO.

*

Traveling like this often ends up as a series of boxes—first the cab of the pickup, then the halved and squared off cylinder of the airplane cabin, and now the box of our SUV, which cruises south from Calgary toward Glacier National Park. We're stopping first in the Alberta town of Waterton, the terminus of our trip, to drop off clothes at the Prince of Wales hotel.

The approach from the high plains of Alberta to the Canadian Rockies is nothing short of spectacular. The plains stretch out right to the base of the range—no foothills, no minor ranges, just a flat vista that without warning spikes upward four and five thousand feet.

And so the mountains loom ahead as you approach from the north. Or perhaps loom is the wrong word. No, the mountains lure you from the north, away from the open, domal sky to an environment of shifting aspect, one where, unlike the plains, you can't always see the weather approach, where the weather is not created elsewhere but is instead built right there.

Blogs are odd, and to post this in sequential order, things move out of succession. This is part one; I will post link to the other parts as I post them.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

To-do: Blog

So I've been having to actually, you know, work, which hasn't been any fun. It's almost like I forgot this was here...

But, for now: to bed. Here's a few pictures from Montana:

Friday, September 15, 2006

Montana (I), no. 2

Note: This is the entire first draft of this entry. Pictures still to come.

The tree trunk and the wall of the pit toilet are only four feet apart, and the pit toilet is only 8 feet tall, and yet I'm the only one who can't wedge himself up the space onto the roof.

I've got a variety of rationalizations for this, of course: I'm dressed improperly for real climbing—in a brown pair of canvas pants that, as a child of the Bay Area, I wear everywhere, all the time; and I'm wearing hiking boots with thick rubber soles that leave a disconnect between foot and underfoot; and I'm not a climber.

This test is not intentionally a test, however, and I'm only trying to get up top because that's where our backpacks are. Our packs are on the roof because we put them there. We put them there, I think, to laugh at me when I couldn't climb onto the roof.

But no matter. I'm not a climber, as I said before, and to tell the truth, I think I'm a little too risk-averse to sheer, thousand-foot drops to ever truly be a climber. Still, I did a fair bit of tree climbing and general boyish mischief to know, deep down, that I should be able to get up there.

*

Here's the plan for the day: 6.3 miles by backpack to the base camp, where we are now; another mile or so to the base of the Cathedral Peak, with only light gear; a thousand (vertical) feet of scree; and then about 800 more (vertical) feet of class 3 and 4 ascents. I think. I haven't really been privy to the plan, since I am close to totally inexperienced as a mountaineer.

Cathedral Peak (elev. 9041') is the only peak on our little 4-day backpacking excursion in the Climbers' Guide to Glacier National Park, which has been and is the only guide we have, other than our eyes, to the mountain. My two partners for this expedition are Bob and Zander, who have taken me along out of the goodness of their hearts and not, as is obvious, due to some sort of innate wilderness talent or USGS 7.5 minute map, which I am wishing we had. Zander and Bob are climbing partners, and though Zander's only been at this for about 3 years, Bob's been at it for 30. Oh, and he's completed 3 ironman triathlons as well.

In theory, we'll be back in camp sometime between 4 and 8 pm, but you have to pack to come down in the dark or, at worst, survive the night on the mountain. Not to be happy, but to survive, which means a set of polypro in the bag, a Goretex jacket, food, 2 liters of water, and a flashlight. It's clear I'm the weak link from the beginning, but hey, they invited me.

*

We leave Flat Top, where we spent the night, at 8:15 in the morning. This is somewhat of a late start for mountaineers—Zander tells a number of stories about having to get up before 4 to summit peaks in the Sierra—but we're traveling in a larger group of six, and getting up at 6 and out by 8 is a little more reasonable for those not ascending Cathedral Peak. Also, we're carrying much of the heavy gear—tents, food, and the like, the things that all six of us need before we split into two groups.

I am indeed ready to go at 7:58. This surprises Zander a little, I think, because I am the last to actually get out of the tent, and almost the last to leave the cooking area for breakfast. I'm always slow to move in the morning, especially when it's cold out, and this morning the temperature hovers around 40 degrees just before dawn.

We're on the trail just after 8:15, moving north at a brisk pace, and Zander and Bob speculate on where the notch to the top actually is. The description says that we cross a “snow field,” but there's no snow to be seen, save for a tiny patch, about 10 feet by 8 feet, just under the striped band of rock at the top of the scree. Bob's betting on a hidden notch with a couvoir behind; Zander's money is on a visible notch further right. As an utter novice, I am left out altogether.

The walk is often spectacular, but not in a photogenic sort of way: We cross from fire zone to forest and back through a long stretch of charred trees and vibrant fireweed. Through the trees, both dead and living, Flat Top falls away and we are encircled by beautiful mountains that float above the haze and low creek beds. It's not the type of thing you can really take an accurate picture of; but, to be fair, you could say the same about most of Glacier.

All along the path lies evidence of a vibrant animal community though we see little fauna besides ourselves: bear scat; coyote and mountain goat droppings; and at one point, a field mouse's head, teeth to the sky, and its nearby internals, but no body otherwise. Bob figures we interrupted a coyote's breakfast, and I figure he might be right.

We make Fifty Mountain Camp just before 11 a.m., my fingers splotched purple from the blueberries and huckleberries we've stopped to eat along the way. Even if there is a fair bit of jollity—and, Bob and Zander being climbers, morbid humor—we are all business. Bob sets up his tent to reserve a camp site; we pack day packs for the climb; eat lunch, which for me is PB&J on a slightly stale cinnamon and raisin bagel; put our food in the bear box on site; and put the aforementioned packs atop the even more aforementioned toilet.

*

The haze finally breaks around noon, and we leave camp just after. We trek through a beautiful meadow with red and yellow grasses, yellow flowers, what appear to be red clovers, and boulders scattered about like children's toys. Zander and Bob now agree where we're aiming for: a small notch, barely visible, climber's left of the snow patch. We mount a small rise and start off trail.

It's not far from the trail to the base of the scree, just a small walk across a pile of loose rock that's come down from the mountain, across a couple of creek beds and a small stream, and then upwards.

Where the scree is still mostly steady with the roots of some small, hardy plants, I'm the fastest moving up the hill. It's easy, I think, though I've always seemed to excel at going up things, both on my feet and my bike. The goat paths aren't hard to spot if you follow one, then find the next, and I find goat droppings three times before the plants disappear, the slope grows steeper, and I begin to falter.

This is about 40% of the way up the thousand feet of scree. I'm no good at this, not naturally: you've got to kick step, Zander coaches me, kick your toes into the rocks and then repeat again as you climb the hill. Leaning forward to scramble, which for me is instinctual, is counter-productive: it loosens the scree, and even when it doesn't, it takes more energy than climbing on two feet alone.

My instinct, on the other hand, is the dash-and-gasp, and it leads only to trouble. The elevation isn't a problem when I'm moving steadily, but here, clambering directly up the slope as rock falls away behind my feet, I have to rest every 35 feet or so upslope to catch my ragged breath. You should stand up straight, but I don't yet have the self-control for that, and crouch low, which pushes more rocks downward.

Finally Zander crosses my path, zigzagging across the scree about 40 feet in front of me. I'm stuck where I am, on a slope that's just too steep for what I'm trying. You just can't go up it straight; there's no purchase. “See if you can just push your toes in and stand,” Zander calls down. I feel very small.

I'm laying prone on the mountain, looking upwards, with my limbs all spread to spread the weight. “There's no way,” I say brusquely. “There's just nowhere to go.” One of my faults, obviously, is that I don't like not being good at things.

Whether intentional or not, Zander slows his ascent, and I am able to angle over to the area he came from, only sliding about 10 feet down to get there. Since I know where he's been, Zander's footsteps are easy to follow. Even better, he's already compacted the rocks where he's stepped, so there's very little slippage as I climb. The last 150 vertical feet are marked by a series of exposed rock to where Bob is already waiting, at the bottom of the striped band of vertical sedimentary rock.

*

After a short break, we traverse across the bottom of the band to the notch where we will climb in. Above us is a large brown rock wall, marked most notably by almost perfectly square cleavage. It almost seems that, if your legs were long enough, that you could walk up parts like a staircase—a staircase with what climbers call exposure, which is your “exposure” to the risk of falling off the mountain entirely.

I have a small amount of difficultly with the traverse as well, but do fine when I make exactly the same steps as Zander, who's mostly making the same steps as Bob. Every so often I ask a stupid question about why we're going here and not there, why this route and not that one.

I get two answers: One is, in essence, that Bob is following his mountaineer's instincts, with 30 years of experience. When they get tired of this answer, it changes to another: “You can go any way you like.” As one might expect, the other routes I see always seem to get me in a little bit of trouble, the rocks fall away too much, or else are just more work than the routes that Bob and Zander choose.

When we get to the couvoir, we find yet more loose rock. I make them stop so I can get water and retape my toes, which are beginning to blister on top, as they lack even the slightest callouses necessary for the type of upwards rubbing that comes with walking up scree.

We advance into the notch, Bob first, then me, then Zander. We don't get far before we hit a section that requires chimneying—a technique involving propping yourself between two walls and climbing. It's like trying to climb a chimney, hence the name.

It takes a long time for Bob and Zander to talk me through the climb. They say nothing, but that brown canvas pair of Dickies pants1 inhibit movement, which makes things harder.

After I get to the top, Zander comes up and says hat the climb is a little more technical than he thought from watching Bob: the footholds are small, loose rock is everywhere, and the hand holds all slant downwards. Bob goes up ahead to scout the next bit, but he thinks that we might have to have the “difficult talk.”

Bob returns, and at this point I am voted off the mountain. Things don't get any easier from here, and the crux—the hardest part of any climb—looms near the summit. Bob and Zander are unequivocal that I shouldn't continue.

Now, I know that I have to trust their judgment and experience, as its what brought me this far; still, I am not happy. It's 2:20 in the afternoon, and with me along, who knows how long it would take to get up, if I could even make it. The last thing these guys want is to take me back in the dark—or worse.

My say is only that where we are is a bad place for me to stop, because if something happens to Bob and Zander, I'm stuck on there. When I say it I'm thinking about continuing 30 more vertical feet to what I think is the top of the striped band, for two reasons: first, and most important, so I can say I got somewhere; and second, so that if I need help I'm not stuck somewhere difficult to spot and with restricted visibility for me.

Zander, though, understands it differently, and, truth be told, better: that I need to return to the scree before they can continue up. He tells me not to feel bad, and that I've just completed my first Class 5 ascent unroped.2 I'm frustrated and mad, partially because I wanted to summit and partially because it feels like I failed. Zander will later give me a rundown of big climbs he's attempted more than once and has yet to summit, including three attempts on Mt. Shasta. Honestly: It doesn't really help.

The thing you tend to forget when climbing rocks: going down is often more difficult than getting up. So Zander climbs back down to help me as I climb back down, making climbing moves I've never done before. Bob puts me on belay, More for confidence than anything else, he says. As I try to make the moves, I feel like I've just been dead weight, which is never a good feeling.

*

The hardest part of the downclimb, for me, is trusting the footholds. I'm wearing boots—though Zander is as well—and because they're not really in the shape of feet, I'm not sure I can trust them, not sure I can center my weight properly. Slippers, in a way, would actually be easier. Bob says, You don't trust your legs yet, but the honest truth is that I trust my legs—just not my feet.

Bob actually offers to just belay me down but I decline. He may want to get rid of me, I think, but I'm going to learn something. Zander helps every foot- and handhold of the way, making sure I don't lean too far forward. It's incredibly helpful to have him there, coaching me, saying, Look down and left, look over, you've almost done it.

It takes me an hour to get back down the scree on my own. Bob tells me to go back down the way we came up, but looking at it, I realize that the exposed rock is present if I just scramble straight down as well, with no traverse. This is an easier descent, but still a mistake—if there's a landslide, no one will know where to look for my body. Or will be looking in the wrong place.

But there's not, and even though I seem to nearly start an out-of-control slide on the way down, I jump aside before it reaches critical mass. Once I return to the stabilized area, I just trample on the plants—I feel guilty about it, a little, but I need to get back and I'm still frustrated.

*

Back at camp, the other members of our party have found the site and the packs, but can't retrieve them. I couldn't get up there either, I say, so I guess we'll just wait till Bob and Zander get back. The stoves and tents are up there, stuck.

But I wander over to the pit toilet building anyway, and look over the space between the tree and the building. I can do this, think: And I can. It's just an easy chimney, a step on the side of the building, another on the trunk of the tree, and then a hop over to the roof. I call, hand the packs down, and am proud of myself.

It's the first time I've been proud of myself all day.

1 You may wonder why someone who indeed has a fair bit of outdoor experience is improperly dressed. Where are my zip-away nylon pants?

I didn't plan on climbing a mountain, so I didn't plan for climbing a mountain. It's as simple as that.

2 Later Bob calls it a “4 plus,” but both agree that the classification is higher than the listed Class 3.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

September 12, 2006 (approximately)

Essays, John D'Agata writes, are costly things. I couldn't agree more.

Monday, September 11, 2006

A beautiful sentence...

From today's NY Times editorial on the fifth anniversary of the September 11th attacks:

When we measure the possibilities created by 9/11 against what we have actually accomplished, it is clear that we have found one way after another to compound the tragedy.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Montana (I)

The tree trunk and the wall of the pit toilet are only four feet apart, and the pit toilet is only 8 feet tall, and yet I'm the only one who can't wedge himself up the space onto the roof.

I've got a variety of rationalizations for this, of course: I'm dressed improperly for real climbing in a brown pair of canvas pants that, as a child of the Bay Area, I wear everywhere, all the time; and I'm wearing hiking boots with thick rubber soles that leave a disconnect between foot and underfoot; and I'm not a climber.

This test is not intentionally a test, however, and I'm only trying to get up top because that's where our backpacks are. Our packs are on the roof because we put them there. We put them there, I think, to laugh at me when I couldn't climb onto the roof.

But no matter. I'm not a climber, as I said before, and to tell the truth, I think I'm a little too risk-averse to sheer, thousand-foot drops to ever truly be a climber. Still, I did a fair bit of tree climbing and general boyish mischief to know, deep down, that I should be able to get up there.

Here's the plan for the day: 6.3 miles by backpack to the base camp, where we are now; another mile or so to the base of the Cathedral Peak, with only light gear; a thousand (vertical) feet ofscreee; and then about 800 more (vertical) feet of class 3 and 4 ascents. I think. I haven't really been privy to the plan, since I am close to totally inexperienced as a mountaineer.

Cathedral Peak (elev. 9041') is the only peak on our little 4-day backpacking excursion in the Climbers' Guide to Glacier National Park, which has been and is the only guide we have, other than our eyes, to the mountain. My two partners for this expedition are Bob and Zander, who have taken me along out of the goodness of their hearts and not, as is obvious, due to some sort of innate wilderness talent or USGS 7.5 minute map, which I am wishing we had. Zander and Bob are climbing partners, and though Zander's only been at this for about 3 years, Bob's been at it for 30. Oh, and he's completed 3 ironman triathlons as well.

In theory, we'll be back in camp sometime between 4 and 8 pm, but you have to pack to come down in the dark or, at worst, survive the night on the mountain. Not to be happy, but to survive, which means a set of polypro in the bag, a Goretex jacket, food, 2 liters of water, and a flashlight. It's clear I'm the weak link from the beginning, but hey, they invited me.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Montana

Yep, another preview post. I'm busy hustling work, what else can I say?

But soon, there will be all sorts of goodness about a littl eadventure up Cathedral Peak in Glacier National Park.

Cheers!

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Back in...Dots, or Something

So I have returned from the wilds of rural Montana, just for the 3.18 of you regular daily visitors I've had since I said I was leaving.

Just so we're clear, here is the itinerary of my life since, say, early May:

And then back to San Francisco for a week. Followed by...

I'm going to post Montana next, for my own reasons. Then, perhaps, the rest of the driving trip.

And then, perhaps, I think I'll rest a little.

By making my brother write for me.

Friday, August 18, 2006

Out of Touch...

This will probably kill the readership once and for all, but I'll be away from the computer until approximately August 30th.

I'll be in Montana, in Glacier National Park, backpacking around and, I hope, not getting eaten alive by grizzly bears.

~Mario

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

A New Index!

My travelogues are now indexed for easy browsing on the left hand side. Thanks for reading!

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

St Augustine, Florida

The Car Saga: Post-Script

Mention the State of Florida to my uncle Lincoln—who is, in the end, a New Yorker— and he'll reply, “Oh, the State of Waiting?” This is not exactly his best joke, but still, you do an awful lot of waiting in Florida.

An awful lot.

Especially if your car is broken and no one quite knows how to fix it.

So my eventual arrival in St. Augustine was something of a miracle, if only because it meant that some sort of waiting had ended. If the car broke again, at least it would break somewhere new, somewhere far from the lonely sprawl of Gibsonton, and if it didn't, well, I could finally get on with my vacation. While driving in absolute fear that the car would indeed break again, of course.

In total I spent three weeks in Florida, and, in all honesty, I'll probably never go back. Florida is for the most part a vacuum of culture, the place people go precisely when they want to go somewhere where there is no pressure to see or watch or do or participate in anything. Gainesville and Tallahassee are home to the University of Florida and Florida State, respectively, but both schools have better track records in football and Playboy's yearly party rankings than in educating students.

And, of course, there are the retirees, who have relocated to what Lincoln also calls Florida “God's Waiting Room.” If you go to Sun City Center, for instance, you'll see retirees driving golf carts around town, to the supermarket, to their friends' houses, and so on, which is all a social design so that those who have lost the ability to drive legally are still mobile. Noble, in a way; but also miserable, because they, and everyone else, should be able to walk. Not that anyone ever does, even the able bodied; and if you do, you are prone to abuse from passing cars.1

So without a car of your own, life can be unpleasant, if not miserable, in Florida, as mine was for much of those three weeks, and as much as one can say miserable when all the necessities—things like food and shelter and water—are available and you're staying with a friend. But even now the car trouble colored my trip ever since, made me travel differently from how I would have liked made me more skittish than the person I wanted to be.

*

After Michael meets me in Arcadia, he is nice enough to buy me dinner at The Clock, a Florida chain of diners that caters mostly to the elderly or the almost-elderly. (Apparently the name of the restaurant is not ironic, as delicious as that might be.) It's the place recommended by the tow truck driver, himself creeping up on retirement age, and while my grilled cheese on squishy white bread is stunningly acceptable, I am thankful that now, with Michael here, the day is just about over.

This sense turns out to be the one thing in the entire car saga that I sense correctly. Outside the garage, a tenth of a mile away, Michael and I transfer everything in my trunk into the trunk of his goldish Camry, which is most everything I've brought along: a pile of books, small blue duffels filled with socks and underwear, a cd case, a plastic tool box of cone wrenches and chain whips and other heavy bicycle tools. The drive takes an hour and fifteen or twenty minutes, and at Michael's we unload everything into a wobbly pyramid in his living room, and plan to get up early the next morning.

The next morning we return to Arcadia to visit the mechanic, who says he's very busy but agrees to check out the problem. The interior of his shop is a rectangular concrete floor with large toolboxes wheeled about, and it appears not to have any lifts, which I find disconcerting. He tends to wander away when I'm talking to him; and makes absolutely no effort to keep me appraised at all of, well, anything, which is okay with Michael since it means he has a legitimate reason for not showing up to work. Still, we show back up at 4:30, and he tells us that he hasn't been able to replicate the problem, and so there will be no charge.

And neither can the mechanic, recommended by Michael's coworkers, in Ruskin, even though the car bucks on the road from Arcadia and on I-75 as Michael tails me back to his work, where we leave the car for the night. Waiting for the mechanic in Ruskin costs three days; and waiting for an appointment at the Nissan dealership in Bradenton, 20 miles south, takes until Monday, which brings my total time without the car to a week, and my time in Florida to 12 days.

The car bucks strongly on the way to the Nissan dealership, and, finally, I am able to demonstrate to a mechanic—well, a technician—the problem. He recognizes it immediately. “The distributor,” he says in a thick Boston accent. He's from Brookline, as it turns out, so for the rest of his ridealong we talk about Massachusetts, where I lived for a few years as a kid.

He tells me that they can only replace the distributor as one unit, which will cost $400 or $500, but he's going to run some tests to make sure first. As Michael drives me home, I am relieved that, even if it's going to be a stupid amount of money to fix the car, it's going to be fixed and I can leave. Soon.

*

According to Hesiod, the ancient Greek poet, hope is the last, and possibly worst, of the sorrows of mankind that Pandora let loose upon the earth. Hope is a comfort but also a delusion, a belief that one can control the future when the future is in the control of the gods alone.

I mention this because, on this particular point, I am inclined to agree with Hesiod. Hesiod may never have been stuck for three weeks in the pretty-much-completely-miserable state of Florida, but I'm sure that he encountered his own troubles among the “thousand or so other horrors spread out among men.” For the next 10 days my life is a cycle of hope, disappointment, and slowly escalating frustration: The car, eventually is fixed, according to the dealer; but I get it, and it doesn't work. Repeat. And repeat. And repeat.

So, like I said, the approach of St. Augustine was something of a miracle, even if I had intended to make it all the way to Savannah but decided instead not to push the car or my own nerves, which made me jump at ever patched seam in the road and every pothole, worried that the car was bucking again.

The most important feature of St. Augustine, obviously, was and is that it is not Tampa. Indeed, it's about 4 hours from Tampa, which is a long time in a car you can't trust. At this point, I think the best I can offer is a text messaging conversation with my mother, whom I had introduced to “texting”2 maybe a week earlier.

MARIO

St. Augustine!

MOM

(RE:) At least it is pretty there .

MARIO

I noticed!

MARIO

Who knew there was something in Florida worth seeing?

MOM

(RE:) You are not out of the woods yet ! When do you leave the state?

MOM

(RE:) You are not out of the woods yet ! When do you leave the state?

MARIO

Tomorrow, I think.

And I did, even giving out a little roller-coaster whoop of joy at the state line. But even though in St. Augustine I walked around the old fortress at dusk and sat to watch the sailboats motor along the intercoastal; and was hit on by the gay bartender at a pizza restaurant, who told me that this is the one safe place for Family in Florida; and took a ghost tour narrated by a disaffected and bored tour guide who kept playing with her lantern while she was talking; and stood next to a family of four from somewhere in the South, who wouldn't stop talking about Tony Stewart all throughout the tour; and the next morning finally dipped my feet in the Atlantic, thus somehow symbolically completing my journey across the country, even if I didn't actually did my feet in the Pacific at the beginning; and toured the oldest house in country with a contractor who gave both myself and the tour guide an explanation of the historical methods of planing wood; I felt listless, like I didn't do anything, didn't see anything, and that, if asked, I wouldn't have anything to say about St. Augustine.

And this, I think, is the best description, best explanation I can give about what the car trouble cost me. More than time, and money, and my ephemeral happiness, what was lost was my sense of humor in unexpected places, and that calmness that let me wait, and wait, and wait for the right detail about a place to reveal itself. It's as if my car—which did, to be fair, give me the right kind of freedom for my trip—replaced joie de vivre with a teenage ennui, the sense that unless I get what I want right now, everything is boring.

But I wasn't bored with St. Augustine; I certainly found enough to see and do. Instead, St. Augustine couldn't offer what I was looking for, what I needed: Calm; safety; some sort of assurance that I didn't have to worry about my car or the trip any longer. This is not a fair criticism, I know, but life were fair we'd all be thousandaires.

To be fair, I doubt anywhere, on that day, could give me what I was looking for.

1 “Why are you walking?!? Asshole! Get a car!”

2 This is a terrible word, and I promise never to use it again. I apologize for using it here. In fact, I apologize for even thinking it.

More Delays That Are My Fault

Sorry for the lack of posting, folks—I've got a little bit of paying work, so I have to put that first, for obvious reasons. The St. Augustine post is more or less ready to go, but I need to take an hour or so at some point to read back through.

Monday, August 14, 2006

Today's Temporary Post

I swear, later today, I'll actually have a new posting about both my car and St. Augustine, Florida. But probably not for a few more hours.

Friday, August 11, 2006

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Celebration, Florida

It's surprising that, during my first hour in Celebration, I find the town kind of pleasant. Well, not kind of—pleasant, despite the oppressive humidity that hasn't let up since I left Gibsonton. This is surprising for two reasons. First, that Celebration is a new, planned community. Second, that its developer is the Walt Disney Company.

I have nothing against Disney in particular. I may or may not be a stockholder, in fact, because my grandmother used to buy my brother and I small bits of stock— shares, or 7 shares, or 1 share—as Christmas presents, leaving the nicely printed and embossed certificates in 8 ½ x 11 envelopes (or occasionally in No. 10's) for us to not play with and give to Dad to put in a safe deposit box. Still, can you imagine living in a community where the wreath on your door is not a standard circle, but three circles joined together to look like Mickey Mouse ears?1

Actually, I have something against Walt Disney, but Walt Disney the man, not Walt Disney Company. Jerome Pohlen's Oddball Florida, which has an entry on Celebration, quotes Walt Disney's vision for EPCOT, that Experimental Prototype Community Of Tomorrow, as “a city that caters to the people as a service function. It will be a planned, controlled community. . . . In EPCOT there will be no landowners and therefore no voting control. People will rent houses instead of buying them. . . . There will be no retirees. Everyone must be employed.” In the 50s Walt was also a rapid “anti-communist,” meaning that he was friendly to Joe McCarthy and House Un-American Activities Committee.

Instead of becoming what Pohlen calls a “voterless, work-until-you're-dead” paradise, EPCOT effectively became a branch of Disneyworld (sp?), and Disney's plans were unfulfilled. Until Celebration, that is. But Celebration doesn't share much of Walt's ideas, instead buying into New Urbanism, the idea that people are actually happier in communities that are walkable, denser, and less sprawling. And this is why, I think, Celebration seems so nice for what it is.

“I thought you might be pulling out before,” says a middle-aged man in a blue polo shirt outside of the Cafe d'Antonio. Celebration isn't really short on parking, but if you need to park less than a block from your destination, sometimes it can involve a lot of waiting. “Your car, I mean, in the parking lot. I thought I could just follow you to a space.” The man is smoking a cigarette casually and looks like he's on break.

Which he is. His name is Steve and he's the Entertainer for a timeshare company, taking the prospects all around town, though he tells me that he makes most of his money these days by flipping real estate, buying properties on eBay and then selling somewhere else. When I ask him why he sells timeshares, he shrugs and says that it's steady, and easy.

Entering Celebration you drive along a long, green stretch of Highway 192, marked by regular palms and, if you look closely, regularly spaced curb cuts. It's actually quite charming, and gives space to the town that adds to its appeal: The space makes the town feel like a discrete area, like a town. But the curb cuts are suspicious.

“I saw the cuts in the sidewalk coming in,” I say and describe the road. “Is all that going to be developed?”

Steve takes a last drag from his cigarette and heads back inside. “Disney'll always develop every square inch they can get their hands on,” he says. “You can count on that.”

Market Street, after two hours in Celebration, is the beginning of my disenchantment. Market Street is the main commercial drag, mixed-use, with housing above the shops, and parking hidden behind the buildings. It's very walkable, and to encourage that, music, mostly smooth jazz, comes from speakers in the sidewalk. Except that it's irritating, and things don't feel very real. But what's there, however bland it is, is not nearly as important as what's not, and indeed, what the town doesn't have at all.

Market Street:

and across the street, moving up now:

So it's mostly souvenirs. But the town doesn't have a hardware store, doesn't have a pharmacy, doesn't have a supermarket. That is, for all the New Urbanist speak, the town is missing the very things that a town needs to survive.

Actually, I misspeak. Let's be fair: The town is missing the very things that people need to survive.

1 Actual Celebration wreaths do, on occasion, look like this.

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Venice, Florida

I am officially calling shenanigans on the Gulf. Water warm enough to bathe in—what's that? I'll tell you what it is—it's an ocean for the weak.

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Estero, Florida

It was in 1869 that Cyrus Teed had his “divine illumination.” The time, generally speaking, was right for divine illuminations: Teed's contemporaries, groups like the Mormons, the Harmonists, and the Oneida Community, all began based on communal property and a certainty that God's work was not yet being carried out on earth. Of course, one former member of the utopian Oneida Community—a man named Charles Guiteau—shot President James Garfield because God commanded him to.

In any case, while the Koreshan Unity began in New York, as did the Mormons, the Oneidans, and many others during the Great Awakening, the Koreshans quickly moved to Chicago. From there, after a gift from homesteader Gustav Damkohler, Teed moved the group to Estero in 1896 to form the New Jerusalem.

Teed was a bit kooky, but his heart was in the right place. He believed himself immortal, for one thing, and when he died in 1908, his followers waited up for days for him to, well, resurrect himself. It didn't happen, and eventually they buried him. For another, he preached that the earth was actually the inside of a hollow sphere with the sun in the middle, which at least one of his members believed until the moon landing in 1969.

Still, many of his ideas are attractive, and the Koreshans did not produce even a failed presidential assassin.1 Teed encouraged learning and the arts, and the Koreshans had schooling for their children, lectures on subjects from music composition to osteopathy, and planned for a lending library, though it was never built. Additionally the Art Hall held orchestra concerts, theater productions, and all sorts of other events for the happiness of the settlers.

But the Koreshans, obviously, died out. The last four members deeded their land to the State of Florida in 1961 in Teed's memory, and the State has since preserved the buildings and grounds to a reasonable degree. But why did the Mormons thrive in Utah and the Koreshans fail in Florida?

The answer, I think, is in reproduction, specifically that the most fervent Koreshan believers did not reproduce while the most fervent Mormons had more children than fingers. Teed divided the Koreshans into two orders: the Cooperative Order, whose members lived outside the settlement and could maintain their families; and the Religious Order, whose members were divided by sex, required to live in the settlement, and celibate.

The Koreshans never numbered more than a few hundred, if that many. With no or few little Koreshans running around, Teed's grand city—New Jerusalem was supposed to be able to accommodate 10 million people—and his grand new religion failed to leave behind more than a handful of machinery, wood frame buildings, and a population of adherents who could protect the settlement from the huge, amoebic strip mall that is growing across the road.

1 On the other hand, the Oneida Community became Oneida, Ltd., which still makes dinnerware today.

Monday, August 07, 2006

Florida (I)

It is my sincere belief that Florida leads the nation in license plates. Numerically, that is. Michael's father—Michael's entire nuclear family has since arrived, and the five of us are now sharing Michael's two-bedroom condo—claims that Florida license plate templates cover the walls of the branches of the Florida DMV, every possible plate there for you to see and compare and buy. Further, there are an impossibly high number of these, he says, a thousand, perhaps. I am a little doubtful that there are this many, but they are everywhere.

What to make of this? No moral, just a contrast.

Florida's view is that the state shouldn't give up easy sources of revenue, like these plates for the Jacksonville Jaguars or Support Education or Save the Manatees or what-have-you. If the customer—here, the driver&$8212wants it, and it is of no additional cost to the state, only good can result. It is, in essence, economics at work.

The other view is that the state is not for sale.

Friday, August 04, 2006

Near Arcadia, Florida

The Car Saga, Part 3

The car bucks a good amount on the way to Lake Placid, rougher and rougher; and then the rain comes. Well, more that the rain comes, and that I drive directly into it.

There is, apparently, a phenomenon that occurs in the middle of Florida, about equidistant from both coasts, in which, because Florida has no elevation, no hills or mountains of any sort,1 moist offshore air from both coasts comes together along the "spine" (if you will) of the peninsula. This combined air is oversaturated with water, and storms result. This is why it rains every afternoon in Orlando, for instance, or so I understand.

Whether I've been misinformed or not—and whether or not I'm misinforming others now—the rain on the way to Lake Placid is torrential. Water covers the road, both puddling in depressions and flowing off to the sides, but I can't see how much because I am, at this point, exceedingly concerned about following the white lines and not driving off the road or into the opposite lane. Still, at 35 mph with the hazards on, I'm being passed by Floridians, mostly in pickups, going 60. In two more minutes the rain comes down so hard that my wipers can barely clear away enough water for me to see anything at all.

After what is assuredly much too much driving without being able to see properly, I pull off of Highway 27 and into a Citgo to wait out the storm. I have company—all the parking spaces by the minimart are now occupied, and a couple of people have parked at the edges of the concrete lot. Hardly anyone gets out of the car. My hope—not knowing anything about cars—is that the rain will help cool the engine and make the car stop bucking.

It's a waiting game, this.

Through the sheets of water flowing over the windshield and the back window and, truth be told, over the side windows as well, I can make out a sign: Welcome to Lake Placid, Town of Murals. Or so I think it says. Or so I want it to say.

After 15 minutes in which the rain has slowed slightly, picked up slightly, and so on in inexorable repetition, I give up. Patience—that is to say, waiting games— have never been a particular strength of mine. Especially when I have nothing to do.

The main road into Lake Placid is no more than two miles farther along Highway 27, though I don't know it at the time. The view along the highway, even in the rain, is a typical Florida jumble of rectangles set back from the road at varying distances, advertising, more than anything else, an incredible surfeit of parking.2 The main road to Lake Placid climbs a small rise to the right, and then descends very gently as you come into town.

And into town I go. After all, it's the one thing that can't possibly be closed, since the murals are outside the buildings. The rain is now intermittent, sometimes a hard spray, sometimes a light sprinkle, and sometimes no more than a faint drizzle that almost evaporates, virga-like, before it reaches the ground, the type of drizzle that you can barely feel on your lips and fingertips but not on your shoulders or the tops of your feet.

I drive slowly, deliberately, through Lake Placid, since I don't really know where I'm going, and the tourist office is closed, since, even though the sun is still high in the sky, it's now after 5 pm. The car is still bucking, the RPMs shooting up and then precipitously dropping, the engine losing torque, but things always seem to recover.

That is, until I have to wait at a stoplight in another downpour. This time, as the car bucks, suddenly the engine goes quiet and all the warning lights—including the seatbelt light—go on. At first I don't really understand what has happened; but then I coast the car around the corner and across four empty parking spaces. I am parked next to the second of the two murals that I see in Lake Placid.

Twenty minutes later, after a call to my mother to ask advice3 and a call to Michael to warn him that I may need him to come get me if the car doesn't make it the two hours back to his house, I am on the road again, following, for some reason, my original plan through Florida rather than the fastest or most populated, and ergo sensible, route. This takes me—or would take me, rather—along Highway 70 to the outskirts of Bradenton, then the last 20 miles north on I-95 to Michael's house in Gibsonton.

But I only make it 20 miles away from Lake Placid. The car is bucking almost constantly, and it makes me sick to my stomach, like being on the world's most uncomfortable roller coaster. The car, now traveling on mostly-dry asphalt in the sunshine, turns itself off at 50 miles per hour. No one is behind me, and cars come so rarely that I think about walking towards Arcadia, the next town. I have no idea how far it is,4 mostly because I have no idea how far I've come from Lake Placid. Soon, however, a police officer rolls up; I am no more than a mile from a Florida State Correctional Institution, so he waits with me for 45 minutes until the tow truck comes to take the car into Arcadia.

This is just the beginning, just one day.

1 Highest point in Florida: Britton Hill, in the panhandle, 345 feet above sea level.

2 The thought occurred to me as I was driving that there may well be more commercial parking spaces in Highlands County, Florida than there are registered vehicles.

3 My parents both read this, which is fine, but it's necessary, I think, to point out the ways in which I unconsciously or semi-consciously try to divvy up calls like this between them. Notice that I called my dad three days earlier with the first bit of car trouble; now I call my mother. Even though I may be, legally, an adult, I'm still trying to triangulate between both parents.

It's possible that I'll always be this way, of course.

4 17 miles.

The view of Florida from my broken-down car.

Sunday, July 30, 2006

Lake Placid, Florida

The Car Saga, Part 2

Three days later I am in my car again. It's a late start for me--I leave Michael's air conditioned house just after noon--and outside the weather is typically oppressive, in the 90s with high humidity, the type of bright sunlight that bleaches the hair on my arms and legs and enough moisture that the condenser for the air conditioning keeps dripping cool water on my feet as I drive, which would be nice if it didn't make my already-slimy feet just that much more slimier.

I meant to get out much earlier, because even at that point I didn't fully trust my car. Even through the vast empty plains in New Mexico and Texas, and through the empty not-so-plains of Utah, I had tried to drive at dusk or, God forbid, at dawn. Anything to not drive in the worst heat of the day, with a used car that might break down at any time.1

So driving during the hottest time of the day was, perhaps, a mistake. Or perhaps not. In any case, the drive to Solomon's Castle, near the town of Ona, was uneventful. Off of I-75, the roads are long and flat, and while they often sweep to one side or another, there's no real reason for this, because there's absolutely no topography that a road needs to avoid. Also, due to the flatness, there are no landmarks, which I suspect makes driving in Florida more difficult for those with a poor sense of direction.

The turnoff for Solomon's castle is maybe two miles before you come to Ona, but traveling on SR 75, it can be hard to believe that you haven't already passed the turnoff, onto a little road that gives off the impression of a dirt road rutted by tire tracks that has only been recently paved. This road--occasionally covered my a canopy of scrub trees, but mostly open--wends through another vast flat expanse, but with more vegetation, until it takes a sidearm to the left and intersects with the road that takes you to Solomon's Castle.

Solomon's Castle, I've read, is the home of a not-that-eccentric named Howard Solomon, who has been building in since 1972. The exterior is entirely covered in aluminum printing plates, which can make it blinding in the Florida sun. It's more a piece of commercial kitsch than folk art, but even knowing this, I decided to make the journey today.

But I don't actually get to see it. The gates are shut and Solomon's Castle is, well, closed. This is because today is Monday, and Solomon's Castle is closed to visitors on Mondays, which I completely failed to notice in either of the two guidebooks that pointed me here. That sucks, I think, and turn the car around. With nothing left to do, I head back to the main road, to continue on toward Ona.

Ona, it should be said, isn't so much a town as it is a gas station, at least as seen from SR 75. A man drives a riding mower along the edge of the asphalt, clipping the high grasses so that, in the event of car trouble, you can safely and easily drive your car off the road and into the drainage ditch on either side. The gas station doesn't take cards at the pump, which might be an example of good business sense in Ona, since the station has no competition and having to walk inside successfully enticed me to buy a couple Jumex fruit nectars.

The car bucks a couple of times, slightly, on the way out toward Zolfo Springs, which is not far from Ona. Zolfo Springs is home to the Cracker Trail Museum, which I believe celebrates the history of Floridians drving cattle along the Cracker Trail from the east side of Florida to Bradenton on the west. Or perhaps the other direction. It's difficult for me to say; I should know, since I've been to the Cracker Trail Museum, but the museum's closed.

This one is not my fault. On the door of the museum, the sign says open; and according to another sign nearby, I am here during open hours. Everything is empty, and the displays outside the small, squat building all seem to be large items donated by people who no longer had a place to put them. I walk around, get bit by a single fire ant--it hurts, a lot--and, after 15 minutes, make toward Lake Placid.

I'm headed toward Lake Placid because the thing to see there--the murals--can't possibly be closed. They're on public buildings, after all. But Lake Placid is similar to Solomon's Castle, in that the murals aren't so much for their own sake as they are a way to advertise the town as a resort destination throughout the South and Midwest. Indeed, apparently the town used to employ--perhaps still does employ--billboard trucks to brand Lake Placid as the "Town of Murals."

(See part 3, above.)

1 The issue, of course, is really that I don't know anything about cars,and specifically that I don't know how to prevent Bad Things from happening to my car. I consider myself pretty easy on my car--no harsh accelerations unless absolutely necessary (like spontaneously merging lanes on a freeway, something that Utah specializes in), proper tire pressure, regular oil changes, and so on--but I have no idea what is actually necessary and what isn't. And no idea what else I should be doing.

Friday, July 28, 2006

Gibsonton, Florida

The Car Saga, Part 1

The car had made it to Gibsonton, only bucking slightly twice and both times just after I had had the spark plug wires inspected and the spark plugs changed at Ahrens Z-Car Specialist in Gainesville, so I could imagine that the problem was gone. “I can’t guarantee that this is the problem,” Don Ahrens had said, “but anything else is going to involve taking apart the engine, and that’ll cost 400 bucks.” Since the spark plugs were marginal when I left California, and since Ahrens had already spent half an hour driving and overdriving along rural Florida roads with me, and since I actually had absolutely no idea why the car was acting up, $97 inclusive had seemed very reasonable.

*

Gibsonton, where Michael lives, is not actually a town, technically, but a census-designated place in a county. It was once famed—if that’s the right word—as the winter home for sideshow performers from the Ringling Brothers circus, which had its winter home in Sarasota, about 30 miles south. In other words—and, I stress, not mine—“Gibtown” was the circus freak capital of the world.

Those days are dying out, just like sideshows themselves. Or the original sideshows, rather: Today the word signifies an illegal drag race that takes place late at night, irregularly, locations changing before the police can find them, souped up cars revving engines and flying through streets that you hope are empty.

Gibsonton couldn’t support this new type of sideshow, not if it wanted to. For one thing, the roads mostly cul-de-sac in beige and white tract homes, or, in the older areas, turn to dirt. The main street is 41, the old Tamiami Trail, which was the main link between Tampa and Miami when it opened in 1926 (?). On 41 you’ll find an area that looks much the same as everything else between Tampa and Naples, really, and probably like a lot of the rest of Florida as well. This is fast roads with no sidewalks and no shoulder; strip malls large and small, anchored by a Publix supermarket or a Dollar General; and the support structures for an automotive world: brake specialists, air conditioning specialists, gas stations, oil change and tune up factories.

The post office in Gibsonton may once have had a counter specially made for dwarves, but even a meek question to the clerk about it will elicit a brusque reply. “That was a long time ago,” she’ll say, and then walk off.

Michael lives in one of the new developments, a gated area named King’s Lake Townhomes. The condo association has just put in a fountain in front, which Michael hates, and the gates don’t really work, and the fees keep increasing. In front of the development is a sidewalk that goes nowhere, ending in small bushes and trees to one side and overgrown grass to the other. Eventually these open spaces may be turned to developments as well, and the sidewalk continued, but a fundamental problem will remain: there isn’t anywhere to walk to.

So while Michael loves his physical place, loves the inside of the apartment, he’s not in love with its location. Mostly when he comes home from work he stays inside. Going to a movie, or biking, or doing a hundred other things all involves a drive. Not that Michael, or anyone else there, is without blame, for their agency is, obviously, their own, but it’s frighteningly easy to understand how you can get caught up in a lifestyle where you never leave your house.

One last thing about the name. It doesn’t fit at all, so much so that it would be shocking, if only it weren’t so typical.1 As a visitor, as someone not used to it, the actual shameless suggestiveness of the name—a kindly king, a lake, a town, a home—was and is surprising. But nothing about it is real. There’s no king, of course, since the development is new; and the lake is really more of a pond that takes a good 18 minutes to circumnavigate by foot; and they aren’t really townhouses so much as row houses, but I suspect the developer, and perhaps the residents, don’t know the difference.

To be fair, to their owners, they are most certainly home.

1 A development nearby—a landlocked development in typical American tract home style—is called Tuscany Bay.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Coming Soon...

I''m sorry the posts have been sporadic lately. The entire saga of my car will come soon, but I'm still finishing it up. With luck, I'll post it this evening.

~Mario

Sunday, July 23, 2006

Bradenton, Florida

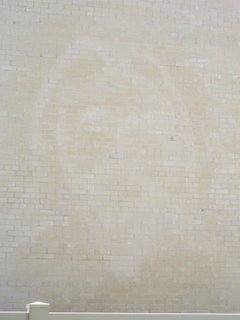

Michael and I were lost a few times along the way, but eventually we found Jesus. He was on the side of a building in Bradenton, which we knew, but finding him was a journey that we'll remember forever.

But only because it took so long for something not so difficult to find.

The story, according to Oddball Florida, is that the workers pressure washing the building discovered the face of Jesus on the church. Soon hundreds of people stopped by to see the miracle. This is on the Palma Sola Presbyterian Church after all, and Protestants aren't so used to finding Jesus' image as Catholics are.

But the image, according to the book, only appears when the brick is wet, so the church has had to hold regular wettings. Michael and I came in midafternoon, between wettings. "There it is!" Michael said when we went around the corner of the church. We took pictures, and in one Michael made the sign of the cross with his water bottles.

Later, Michael suspects that my car breaks down because we were so blasphemous.